Day 7

Today

- Recursion Practice

- Fractal drawing in Turtle World

MP2 Kickoff Survey

Please fill out the Reflection and Teaming Survey #1. This survey will help us get a sense of how SoftDes is going for you and help prepare you for the team-based projects that will be coming later in the course.

Reading Journal Debrief

First, with two other people sitting next to you, make sure you clarify any problems you ran into on the reading journal.

Next, with your same group, read through some sample solutions to the is_palindrome and is_power functions. For each solution answer the following questions.

- Is it correct?

- How readable is it? Note any changes that you think would improve the readability of the solution.

From Three Questions About Each Bug You Find:

- Is this mistake somewhere else also?

- What next bug is hidden behind this one?

- What should I do to prevent bugs like this?

What do you think about the effectiveness of these three questions? What questions do you ask yourself when debugging?

Recursion Practice

Pascal’s Triangle

Write a function called choose that takes two integer, n and k, and returns the number of ways to choose k items from a set of n (this is also known as the number of combinations of k items from a pool of n). Your solution should be implemented recursively using Pascal’s rule.

Levenshtein Distance

Write a function called levenshtein_distance that takes as input two strings

and returns the Levenshtein

distance between the two

strings. Intuitively, the Levenshtein distance is the minimum number of edit

operations to transform one string into the other (for this reason Levenshtein

distance is sometimes called “edit distance”). These edits can either be

insertions, deletions, or substitutions. Note that Levenshtein distance is

similar to Hamming distance,

but works for strings of differing lengths

Here are some examples of these operations:

- kitten → sitten (substitution of

sfork) - sitten → sittin (substitution of

ifore) - sittin → sitting (insertion of

gat the end).

While this function seems initially daunting, it admits a very compact recursive solution. You can either work on your own to see the recursive solution, or use the recursive solution given in the Wikipedia article.

We will be memoizing this function in the next reading journal to make it more computationally efficient.

Making change

Write a program that takes as input a number of cents, n, along with the denominations of some coins, d, and outputs the number of unique ways that change can be made for n cents using the coins d.

For example:

make_change(10, [1, 5, 10]) # -> 4

Specifically:

- 10 pennies

- 2 nickels

- 1 nickel 5 pennies

- 1 dime

Turtle World

Today we will be combining our adventures with turtles with our adventures with recursion. The results will astound you!

Teleportation, Cloning, and Other Unethical Experiments on Turtles

In addition to the what you did on your day 5 reading journal and in the day 6 class activity, a few other Turtle Tricks that may prove useful.

A Turtle is a Python object, which we will learn more about next week. Turtles

have methods, which we can call to inspect change their behavior. One trick that will be useful here, which you saw in shapes.py but may not have thought about much, is the speed() function. The speed() function can be used to speed up slowpoke Turtles. While it seems weird that a speedy turtle would have a speed of 0, in this case the input 0 is reserved for having the turtle go as fast as possible (remember, when in doubt, check the documentation).

import turtle

speedy = turtle.Turtle()

speedy.speed(0)

Other important Turtle methods include xcor() and ycor() position, and

heading().

Read more about turtles here.

Since Turtles are simple creatures, mainly defined by their current position and heading, we can “clone” them by reading these values and using them to direct a new Turtle.

leo = turtle.Turtle()

# leo does some arbitrary drawing (e.g., makes a 45 degree angle)

leo.fd(100)

leo.lt(45)

leo.fd(100)

# Create a new Turtle with the same attributes as the first

don = turtle.Turtle()

don.penup()

don.setx(leo.xcor())

don.sety(leo.ycor())

don.setheading(leo.heading())

if leo.isdown():

don.pendown()

# don.bandana_color = "purple" # TODO: Ninja functionality not yet implemented

As an exercise, encapsulate this functionality in a clone function that

takes a Turtle argument and returns a new Turtle with the same position

and heading, leaving the original Turtle untouched.

Fractals

Fractals are geometrical constructions that display self-similar repeated patterns at every scale as you zoom in. They are often extremely beautiful, and are found throughout nature. Fractals are also useful across many fields, from antenna engineering to poetry to finance. Check out Yale’s Panorama of Fractals and their Uses for more examples.

Today, we will teach our turtles to draw fractal shapes using recursion. A

very cool recursive drawing we can create is called the snowflake curve (or

Koch snowflake). To get

started, let’s write a function called snow_flake_side with the following

signature:

def snow_flake_side(turtle, length, level):

"""Draw a side of the snowflake curve with side length length and recursion

depth of level"""

The snow_flake_side function should have a base case that draws the following image:

The recursive step should replace each of the line segments above with a

snow_flake_side with size length / 3.0 and recursion depth level - 1. Take

some time to work on this and then we’ll discuss as a group.

Once you have completed your snow_flake_side function, create a function

called snow_flake that draws the whole snowflake.

Recursive Trees

Next, we will draw a tree using recursion. Define a function called

recursive_tree that takes as input a turtle, a branch length, and a

recursion depth and draws the recursive tree to the canvas.

def recursive_tree(turtle, branch_length, level):

"""Draw a tree with branch length branch_length and recursion depth of level

"""

The base case is:

This structure is given by moving forward branch_length steps (assuming the

turtle has the correct orientation).

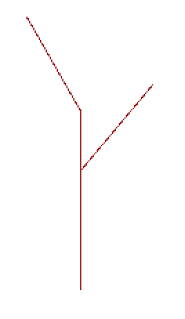

For the recursive step, you should:

- Draw the line as above

- Clone your turtle

- Turn the new turtle left 30 degrees

- Recurse using the cloned turtle to draw a tree with branch length

branch_length * 0.6and depth `level - 1 - Hide the cloned turtle using the

hideturtlemethod - Back the original turtle up

branch_length / 3.0 - Clone your turtle

- Turn the new turtle right 40 degrees

- Recurse using the cloned turtle to draw a tree with branch length

branch_length * 0.64and depthlevel - 1 - Hide the cloned turtle using the

hideturtlemethod

After implementing the recursive step, if you set level to 1 more than the

base case (which will either be 1 or 2 depending on what level you consider

the base case), you will get the following picture:

Once you’ve built your recursive_tree function, try making a few

enhancements:

- Make the base case change the pen color for the turtle to green (this will simulate the appearance of leaves if you do a high enough depth)

- Add some randomness to the degree of left turn, right turn, and scaling so that you get more naturalistic looking trees

- Add more than two branches

More Recursion

The Koch snowflake and our recursive tree are both part of a more general class of curves called L-systems (Lindenmayer Systems). Next, read the linked Wikipedia article on L-systems and try to implement Sierpinski’s triangle and fractal plant.

Hint 1: For Sierpinski’s triangle you will want to create a function to generate both symbols A and B and have them call each other.

Hint 2: For the fractal plant you should create the following functions to

save and then restore then Turtle’s state (symbols [ and ] respectively):

def save_turtle_state(turtle_states, t):

turtle_states.append((t.xcor(), t.ycor(), t.heading()))

def restore_turtle_state(turtle_states, t):

s = turtle_states.pop()

t.penup()

t.setx(s[0])

t.sety(s[1])

t.setheading(s[2])

t.pendown()